On several occasions, I have outlined a model for the sort of society I not only hope will emerge from the crisis and collapse of the Capitalist order, but which I actually believe WILL emerge.

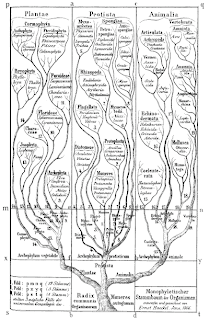

That, I guess, is an act of faith. A belief that the outlook I have is correct. That progress is governed by evolutionary laws and that therefore, the society I dream of is not just the one I HOPE will emerge, but I believe that the underlying positive qualities of the species as a whole and it's ability to adapt and change in a good way will outweigh it's negative more primal instincts and that we will rise to the challenge.

And I've used the term Utopia for that vision. I've described it as a twenty second century Utopia.

In this, I think, both myself and Marx would agree. One of my beliefs- perhaps arrogantly- is that if Marx were around today, he'd be nodding his head at some of my writings and agreeing. Occasionally, he'd correct me on what he meant, but also he'd be saying 'Well, these are things I couldn't have foreseen, so you've taken that point further than I could have done'. Overall, however, I think he'd be relatively pleased at my interpretation of his theories. Glad perhaps, that SOMEONE bothered to understand them properly.

Because the vision of Utopia I describe, is of course the one that Marx was talking about. The collapse of Capitalism and the state of things as they stand, again, is what Marx was predicting. Nevertheless, we now come to something else that Marx described- the dialectic conflict.

Because if one looks, one clearly sees that the Utopia I describe- and actually the one which I think most fits Marx vision- has many, many features which show the blending of the thesis and the antithesis to create a new synthesis. It's actually a communistic system which delivers GREATER individual freedom than Capitalism does. Because it involves the pooling of resources to FREE humanity. It actually retains many of the good points of Capitalism.

And several commenters in the past have suggested that such a society would then be static. That there would be nothing to strive for.

This of course, would not be the case. The new thesis- the Utopia that was being perfected, would now itself show up as glaringly imperfect. Just not in ways that can quite be comprehended yet. That isn't to say that the synthesis won't be correct. The 'Utopia' will be better suited to drive human needs forward and improve quality of life. But in doing so, it will create NEW challenges, a new antithesis. Challenges that one day it will be unable to meet itself. And a new structural change will become increasingly needed. Another radical shift in the human way of doing things. A new and better Utopia, even more perfect will be seen to be possible, and my so-called Utopia described on this blog in the past will seem- backward. Flawed. Archaic. Anachronistic. Inefficient. Unable to answer the challenges of the twenty third and twenty fourth centuries.

It will no longer be Utopia. Or it will be, by our standards. But it's dystopian edge will have started to show. But it will reach a point where not overhauling it, allowing it to carry on will no longer lead to an INCREASE in human prosperity, but a DECREASE in it. We'll be back to where we are now, in relative terms. Of course, in a sense we won't be. Quality of life will be much higher than it now. But it just won't be improving any more and the danger of it slipping back to what it is now or even lower will be present.

What Marx understood was what economists and historians of the nineteenth century were dimly starting to understand, the basis for my historical series on human systematic development. That revolutions aren't merely political, they are phasal shifts. The eighteenth century was a phasal shift. Human systems were not up to meeting the challenges facing them. Human knowledge was capable of aspiring to more than the system could deliver. The wildest dreams of humanity could be achieved, just not as things were.

Let's not forget, it WAS achieved. Look at the prophets of Liberal Capitalism. If John Locke could have seen the London of 1900, he'd have thought Utopia had come. The system of living brought about by the societal changes of the Capitalist era, had created a society that was Utopian- at least in England- by seventeenth century standards. What Locke could not have foreseen was the new challenges that would bring, why it was that such a system could not continue forever. Why even it's pinnacle, the Utopia of Capitalism was on the wane.

Monarchy and Mercantilism were not up to delivering the changes needed in eighteenth century Europe. If you wanted to create a Europe where people could have freedom of conscience, where people could enjoy increased living standards, where people born had a good chance of themselves living to adulthood, where the old and the sick were cared for, a huge expansion of the system of production and distribution needed to take place. And that could only take place by vastly increasing the ability of individuals to partake of this system. A system at least had to be devised whereby expansion of the infrastructure could take place unhindered and those involved had real decision making power. A degree of efficiency needed to be a part of it. Government and power could no longer be tied to possession of huge landed estates. A system of circulating resources with ease needed to be established and one in which planning of the overall whole was in the hands of those involved.

Royal trading monopolies and grants to nobleman of tracts of land were not going to turn the American wilderness into teaming states of human civilisation. Telegraph lines were not going to be laid down across the Atlantic if only the king is allowed to use them.

The change that was needed was a system which expanded the amount of people involved in decision making processes and removed constraints on expansion of the infrastructure. So the long terms goals of Capitalism were clear. More infrastructure, better infrastructure, more say by more people on how things are done, get as many people involved as you can in this group effort. Work smarter, not harder. And the more we build up, the more of our efforts we can afford to spend on things at one time we couldn't have.

What Marx realised was that all these changes were good. Amazing changes that would change the world for the better. But would create new problems unforeseen at the start. And in themselves would not be the ultimate answer.

Because at the start, these ideas only mattered in Christendom, or what had been Christendom. The Utopia that was being envisaged was just the West. But of course, the thrust of this change would be to create a global society, Marx could see that. And then the limits would be reached.

What Marx foresaw was that at the end of it, a very unequal infrastructure would exist. In the West, there would be no need to expand it any more. Indeed, the problem would be in finding people work to do, because Capitalism had started off by getting people to sell their labour at a fixed rate. But technology would mean that as time progressed so much more was produced from their labours that the system produced far more goods than could be bought by the people who produced them. Because they weren't being paid a share of the produce, they were being paid in tokens relevant to how much it cost to produce those goods a very long time ago. So most of the profits of this system would consist of unused tokens, or more accurately, would simply be guzzled up in interest payments by the banks who funded the whole thing. The banks indeed, would have become a block on human progress because over the years they would have increased their share of the world at everyone else's expense. No wealth could be added any more to the economy, because there was no more territory. No more consumers. Improvement would always be possible, finding better ways to use what was in position, but there were no longer any new markets to bleed dry. So the banks would now be bleeding everybody. Every year, everybody not in a position to lend money would get poorer and those who could, richer. A perpetually increasing relative poverty gap.

Also, the infrastructure would have been unequally set up. Skewed. In the West, it would serve the people, to produce and distribute to them. In other parts of the world, that would have been secondary. The first concern was to bring goods to the west. Development of those regions for the benefit of the people would happen, but only secondarily. And once the limits of the expansion were reached- would feeze.

By the way, did you know Africa only possesses ONE railway route that doesn't lead from primary material rich areas to the coast? Only one railway line exist that was actually built to unite places inland and was built without shipping materials in mind.

The Russians paid for it in the seventies. It links Zambia to Tanzania.

So the last places to be developed would possess an infrastructure whose prime purpose was to export their materials outward. And lack many basic services that those who designed their infrastructure possessed. A global caste system would now exist, to replace the old one. Those in the west would all feel equal, that life in their countries was good. No class system, apparently.

But there would be, globally. A global Aristocracy- the corporations- a small global bourgeoisie- the western citizenry- and a huge global underclass. Still peasants, basically. The west would have become all middle class, everywhere else would all be peasants. And this of course, would be a highly unstable world. It would be France before 1789, but on a global scale.

And of course, the real point is, when the bourgeoisie realise that they don't lose out from the change. The peasants or the proletariat will indeed get much richer. But without the bourgeoisie getting poorer. Because the systematic change in view will lead to a better SYSTEM. Better at producing and distributing. It will be more efficient.

Which is where we are now. Or getting there.

So, the Utopia of the twenty second century. Will it be delivering an improvement?

Yes. I think when we have abolished money and put in place an equal infrastructure across the globe, we will look at the token system anew. And we will divide production in to two parts.

One part, we'll call taxation. The amount of work the citizen has to do to reach tax freedom, basically. Now of course, right now, most of the work we do is pointless. Unnecessary. It simply serves to move tokens around. So what this change will mean is that the value of work, from the point of view of the citizen, will be increased. The cost of everything won't have the cost of millions of hours of superfluous labour factored in.

So we'll work out how many man hours are needed to provide a subsistence life, in twenty first century terms for all. To pay for all things we now pay for out of taxation. And to provide housing and food. The cost of everything that you HAVE to pay for now. What we'll do, is we'll allocate ALL of that, to taxation. And then work out how many hours a week everyone actually has to work. My estimate is that it's about ten hours.

As for the rest of what you spend your money on, I guess we'll pay tokens to people for any surplus they put in. Though of course, those tokens will actually be entitling one to a share of the surplus. So people will get considerably more value for their efforts. If you want lots of goods, do lots of extra hours, or do something for which the tokens awarded are more, learn a skill. So it would still have the incentives of Capitalism. The more you put in, the more you got. What we'd simply be doing is better managing the basic bit. Everyone putting in equally there, a flat rate. Ten compulsory hours to keep the fabric of society to the standard we want it. Then with the rest, go buy CDs, or a boat, or just beer if you want.

The logic of this change is of course, the vast amounts of free time. To gain luxury goods and materials won't involve much work. with things as they stood, there would be no point in ANYONE working forty hours a week. They'd acquire far too many tokens to be able to do anything with. Since no one could buy bits of the infrastructure any more, the point of acquiring more tokens than you yourself could ever spend, would be limited.

So a new dynamic would enter human thinking.

Nowadays, when we say a project will cost too much, what we mean is we can't access the basic resource which governs everything. Man hours. Because everything else depends on that. If you have the human energy free, you can do anything. When we say 'Terraforming Venus isn't doable under current levels of technology in anything less than a few centuries' what we mean is, we haven't got vast reserves of free human energy.

Of course, in a world where everybody does ten hours work a work to ensure that everybody lives in greater comfort than most people do today and then another ten hours a week on average to satisfy their individual needs for material goods and other comforts, then things change.

Human society might well say; what we can now afford to do is double the compulsory output. To twenty hours a week. People are still not going to be working anywhere near as much as their ancestors were. But we'll be producing twice as much.

What do we need to do that for? Why the need for such a vast increase in productivity? Well, because we can. Because most people would see that now the point has been reached where all technological development is exponential. Working to live isn't a burden. Working to acquire the good things in life isn't that much work either. Fixing the contribution to the species at twenty hours means that the combined efforts can lead to improvements and projects not before thought feasible. The doubling of the power of the species, basically.

So it propels an advance that only this new system could provide. Democratic Communism now leads to colonisation of the solar system becoming practical. Mankind can devote as much time to doing all the things it once couldn't afford as it does to all things that today are considered the basic essentials.

Problems such as overpopulation and the like disappear- temporarily.

And by our standards, Utopia has been reached.

By 2200, everybody does twenty hours compulsory work, everybody lives in comfort, almost all basic work is handled communally. Everybody lives as an individual within their communities and everybody works extra hours to buy the good things, the surplus luxuries of the system. Pleasure.

Because humanity can afford it. It can afford to sit around and think 'Titan, next year, what do you think? How long would it take to terraform that? Thirty years, maybe? If that?'

So when would the point be reached when something radical needed to be changed? What challenges could destabilise this system?

When would it start to reach hurdles that could only be overcome by overhauling large parts of the human way of life?

Marx of course, never got that far. Marx predicted the challenges that the current phase would not be able to meet and the flaws which would undo it.

Is it possible to see the challenges the new system will throw up?

Yes, I think it is. At the start of course, they won't be flaws. They will be necessary features of it, things that will drive it, just as Interest drove Capitalism. And I don't think Marx could have seen- from where he was standing- the challenges the next two centuries- assuming of course Utopia happens- will bring.

And what the NEXT phasal shift will involve.

Is there much point in speculating that far ahead?

Yes, I think there is.

But not in this post :)